Monday, October 15, 2012

NYFF 2012: The Case for Cinema

Cinema, as an art, is not a modern human innovation. It is not an invention. The technical means by which we conceive and project it have emerged in the last century, true, but the need for it and desire for its magic has existed since the dawn of man. Some thirty-odd millennia-old cave drawings from our earliest ancestors show buffalo with many legs, presumably to create the illusion of movement of a stampeding herd when torches of light were swayed over the pictures from side to side. In 2012, it has been proclaimed that cinema is dead. Film stock is being phased out in favor of digital cameras, which some think of as little more than small computers. It is possible now to watch Lawrence of Arabia on your smartphone. Movie theater attendance has dwindled since the onset of remote controls and VCRs.

As the 50th New York Film Festival draws to a close tonight, it’s proven to be an unqualified success. Not just in terms of the publicity gained by unveiling Oscar hopefuls like Lincoln or Flight, but in showcasing a selection of films that, in 2012, actually push the boundaries of cinematic possibility and offer an exciting and hopeful future.

The festival opened with Ang Lee’s Life of Pi, the director’s most daring venture yet — dipping his toes in 3D technology and heavy CGI amidst the thematic density of Yann Martel’s novel. The business of Hollywood seems to have appropriated such technologies in a depressingly cynical way, going so far as to retrofit 3D onto films that were made to be seen in simply two dimensions just for the sake of maximizing their profits. But Ang Lee shows us the true potential of cinematic expression possible with these new means of filmmaking. As a spectacle, Life of Pi is unmatched. The height of the film is in the turning point of the ship sinking scene, which is equally harrowing and horrifying. The film swept me up and immersed me in a theatrical experience that I could feel would be remembered fondly in 10, 15, 20 years and forward as a moment of moviegoing marvel.

It’s what one might call an “event” film, the kind Hollywood executives try to put out each Summer to keep people wanting to see films in the theater rather than illegally streaming it to their laptop through the allure of 3D and/or IMAX projection. It’s the thrill of watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master in 70mm and feeling like you’re watching a cinema in its purest form. But no director heretofore — not James Cameron, not Chris Nolan, not even Martin Scorsese — has felt out the potential for depth and spectacle with these tools more comprehensively that Ang Lee has here, not only advancing CG technology to new heights with the creation of the tiger but in cracking open new possibility for the future of film going into a digital age.

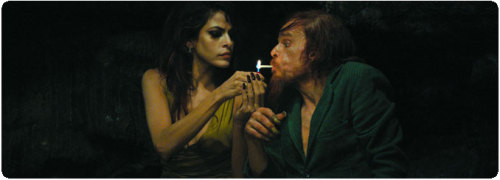

Also playing with the digital format, albeit begrudgingly, was Leos Carax’s return to filmmaking since Pola X in the 90s. Holy Motors opens with Carax himself awaking and entering a theater full of spectators as we enter his strange abstract world of a man with many worlds himself, a job of many occupations, and no shortage of faces to put on. It plays largely like a lament of this new age, between people’s abilities to be anyone they please through internet anonymity to intercuts of very early film yearning for a time when cameras were bigger than you (when now they’re smaller than your head, and everywhere you turn). Consistently mind-ripping sequences offer a feeling that they’re instantly iconic, tearing to shreds every standard of film you assume and creating a mad, nonsensical masterwork that keeps you at the edge of your seat for watching something exciting and new unfold in front of you. Sequences played out with a sense they’d instantly become iconic. You come to the safe conclusion that you never know what’s going to happen next, which is a feeling so fresh and so thrilling — to know you’re witness to a game changer. Jean-Luc Godard once noted that if cinema had never been invented, Nicholas Ray would have invented it. Suffice to say, I think the very same applies to Carax.

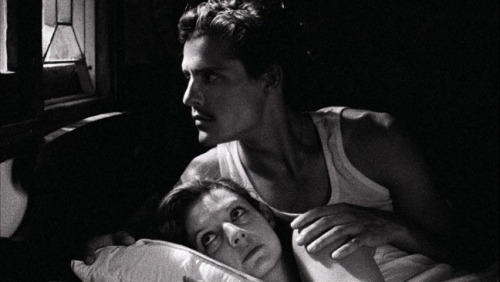

Perhaps the very finest film to screen at the festival was Miguel Gomes’ dreamily lovely Tabu. Gomes, working with film, actually uses the older tools at his disposal to paint a portrait of Western humanity between past and present, switching between 35mm and 16mm between the film’s two acts. The film in the present is in the more realistic (though black and white) 35mm print focusing on a present day woman in Lisbon whose elderly neighbor is nearing the end of her life with a maid hired by her daughter that she is deeply paranoid of. The film touches on social contexts explored in the second half of the woman’s earlier life in a Portuguese colony in Africa in grainy 16mm offering a dream-like reflection of a story that delves into unabashed melodrama that reflects on the past, its relevance to the present, and the general universality of human emotion. It works as engrossing entertainment as well as it does in its depths of commentary (pertaining to race, class, history, gender, age, etc.) and is a real achievement.

Also employing some old school film stock is Pablo Lorrain’s No, which looks like a 1980s home video cassette recording that Lorrain then brilliantly intercuts with actual archival footage looking very much the same. Documenting the “No” campaign in the 1988 Chilean plebiscite against General Pinochet, the film uses the actual television spots run on both sides and footage of protests that show the brutality of Pinochet’s regime — making so much more powerful the actual staged events of the film featuring a fine performance by Gael Garcia Bernal. The film’s fresh and fascinating use of cinema lends to a much more explicitly political message than that of Tabu, but the film is similarly so light-hearted and rather fun around its edges.

The films at this year’s festival ranged widely in genre, tone, style; some used digital, some used film. But they all unite in confirming the hope for the future of film — for its possibilities, its potential, its usefulness, and the value of still going to see movies like this in going forward. Many people seem confuse a lack of a clear future path with having no future at all. What is actually the case is something a lot more exciting, and a lot more fascinating than the more foreseeable path! People can make films at the palms of their hands and upload them to youtube. Amateurs like myself could access these works publicly and write up my own critiques of them. It can be argued, in fact, that we’re witnessing the dawn of a new emerging golden age of film. A golden age where everyday people from all around the world are creating new and interesting works of art with new and rapidly advancing formats and technologies that bring us well past the age of waving fire-lit torches across a simple painting to mimic the basic magic of a moving image, and into the 21st century with an evolving and expanding understanding of the cinematic form. Read more!

Friday, June 8, 2012

Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

In the vast spectrum of film history, it's difficult to pinpoint precisely where the ceiling stands for the medium's fullest realization of potential. Many a maestro have undertaken ambitious stabs at creating immense behemoths of cinematic pièces de résistance, but so few were able to capture the depth of beauty inherent in the poetic simplicity of Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali. There's a limited setting, only a few characters, and a storyline too simple to even aptly summarize. But its dreamy realism quickly compels one into insouciance of this matter, as you're drawn into this third world village as if you've lived there all your life.

Ray's camera offers a hypnotizing gaze into the world of these characters going through the simplest tasks of their day. A young boy named Apu and his older sister Durga play together in the fields. Their elderly (to the point of looking skeletal) great aunt Indir shares the home with their mother, Sarbajaya, increasingly aggravated by her old aunt-in-law as she tries to provide for her children while their educated father, Harihar, ventures into the distant cities to to earn money as his family falls deeper into abject poverty. Anyone wishing to pursue film should at once feel shocked, thrilled, and horrified watching this naturalism unfold as if a camera were simply placed unfussily in front of these people — breathing, eating, playing, talking, fighting, loving, dying, and living — and not, as is the actual case, by a first time director working with an inexperienced crew and a group of amateur actors.

But therein lies the true magic of this film which, truly, is the apex of what cinema is capable of achieving. It lies in its transportive properties that lulls you into complete absorption of another world and another time completely removed from your own. It's in the emotional mirror Ray holds up with each shot of his characters that you instinctively just seem to somehow understand thoroughly on a very human level, even when one character is at odds with another. It's in the wonderment one feels going on this journey with the little boy who's lived a life free of any modern technology or privileged convenience as his eyes widen with astonished exhilaration looking up to watch a train pass by for the very first time in his young life, or as he watches a show from a passing theater troupe in awe of the escapism and ambitious dreams for himself it would inspire.

And like with many great works of art, the impact of everything accomplished seems nearly invisible until experienced fully in the sum of its parts. Each passing moment appears inconsequential at first until a devastating final shot alone puts into perspective the entirety of the journey one goes through with the characters of this film. Sitar player Ravi Shankar's relatively minimalist soundtrack somehow manages to help offer the illusion of a full sensory experience, and the cinematic flourishes seem modest if not entirely non-existent. But there is a heart that pulsates rhythmically throughout the entire film, seamlessly, without the slightest bit of fuss to the most profound of consequences that evidences Satyajit Ray's talent as one of the most naturally masterful directors who ever lived. Akira Kurosawa once said of this film that "[i]t is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river...Without the least effort and without any sudden jerks, Ray paints his picture, but its effect on the audience is to stir up deep passions. How does he achieve this? There is nothing irrelevant or haphazard in his cinematographic technique. In that lies the secret of its excellence."

Monday, April 30, 2012

Calling The Tree of Life a "religious film"

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Month early Cannes predictions

Grand Prix: Beyond the Hills by Cristian Mungiu

Jury Prize: Après la bataille by Yousry Nasrallah

Best Director: David Cronenberg for Cosmopolis

Best Actor: Tadashi Okuno for Like Someone in Love

Best Actress: Marion Cotillard for Rust and Bone

Best Screenplay: Mike Nichols for Mud

FIRPRESCI Prize: Amour by Michael Haneke

Let's see how this compares with my predictions closer to it, and how it actually unfolds. Read more!

Friday, March 23, 2012

Theater: Death of a Salesman

There's fewer pleasures in life for someone infatuated with performance art than watching a performer live at the top of their game hitting their sweet spot in stride. I've arguably seen it before in Cate Blanchett doing Blanche DuBois in Liv Ullman's production of A Streetcar Named Desire. I've seen Lauren Brown do "There Are Worse Things I Could Do" in my high school's production of Grease (trust me, it was incredible). I sadly don't get the treat very often of going to the theater, however, sad though it is that I've missed out on Jennifer Holiday performing the original "And I Am Telling You," Paul Robeson as Othello, or, more recently, Mark Rylance in Jerusalem.

Never though have I witnessed such explosive energy as I had in the current Broadway production of Death of a Salesman. The casting had understandably aroused some questions, between Philip Seymour Hoffman seeming too young and intellectual for the part and Andrew Garfield too meek. Linda Emond went relatively unscathed in the public scrutiny for lack of relative career exposure, though she may well find herself a Tony winner come June for her fantastic work as an aging woman who has nothing left but to stand by her slowly slipping husband.

All three central actors played their roles as unconventionally as their very casting choices, shedding light on different dimensions to their characters not often seen in the countless productions of this American classic before, utilizing their various "sweet spots" as actors to open up new possibilities of interpretation. For Philip Seymour Hoffman, it's less the old world weariness that Lee J. Cobb brought to the role in spades as it is his ability to wear a self-pity on his sleeve even as Willy himself outwardly denies it — which makes it that much more heartbreaking when his worst apparent fears become realized.

For Andrew Garfield, it's a deeply internalized sense of quiet repression that intelligently expressed so much of how Miller wrote Bif in his strained relationship with his father, his defeatist attitude towards settling down with a career, his remorse over the way things have gone. His arc continued to what Garfield does best in an explosive climax where he gradually breaks down with such technical skill that left everyone in the theater sniffling as they left the theater. Despite a delicate frame and innate sensitivity, the sheer force of his presence at such emotional peaks secures him comfortably in the top tier of actors in his generation that I'd be surprised doesn't deliver him a Tony Award this year.

The combined electricity of all these actors under Mike Nichols' seasoned direction is such a treat, emotionally devastating though it is, and leaves you rethinking the themes of Arthur Miller's masterpieces long after the curtains close. Read more!

Sunday, January 29, 2012

A Love Letter

The night that Michel Hazanavicius wrapped up the race with a DGA win, I found myself rewatching The Artist for the first time since I'd first seen it at the New York Film Festival in around October. I had never minded it sweeping the awards, and it was never quite my first choice but I always admired it and found it to be perfectly pleasant and clever.

But such may have been short selling it, I believe. Mark Harris jokes that the film has been labeled one of nostalgia falsely considering most of us were not around for the era the film chronicles, thus we can't feel nostalgic about it. But I rewatched it just feeling nostalgic for having watched it the first time a few months ago, and nearly every image was memorable in a way you just don't find with cinema these days. The Artist will be a film forever remembered as a classic precisely because of that — because you can say, "oh, remember that scene in the film?" with nearly every scene and it'll be clear and crisp in your mind as the day you'd first seen it, whether you realize it or not, the same way you can with so many gems of the most classic Hollywood films. Hazanavicius deserves full credit for expressing this story through such salient, memorable images throughout the film.

It's very much a cinematic picture in it's own right — it wouldn't even be fair to call it a period piece, since I believe the film doesn't actually take place in a real world. It takes place within the realm and universe of a silent film from that era, its characters are characters themselves from the kind of movies from that time, and more than just sheer cute gimmick, it is such a passionate homage to those films and a beautiful love letter.

It's no wonder, then, that this will almost certainly be the most deserving Best Picture winner, in my mind, since Slumdog Millionaire a few years ago. Like The Artist, Slumdog was a love letter to the Indian culture and likewise, brilliantly, infused elements far and wide from it ranging from the country's booming rise in globalized industry and development to the very conventions and sentimentality in the films of Bollywood that so many of the impoverished populations escape into with joy, dancing, sadness, redemption, morality, and more. Audiences fell for Slumdog Millionaire for the same reason they'd fall for any Bollywood film as so many now love and will come to love The Artist for the same reason classic Hollywood films came to define our culture in the past century. Read more!

Monday, January 23, 2012

Final Oscar Predictions

The Artist

The Descendants

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

The Help

Hugo

Midnight in Paris

Moneyball

Best Director:

Woody Allen, Midnight in Paris

David Fincher, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

Michel Hazanavicius, The Artist

Alexander Payne, The Descendants

Martin Scorsese, Hugo

Best Actor in a Leading Role:

Démian Bichir, A Better Life

George Clooney, The Descendants

Jean Dujardin, The Artist

Michael Fassbender, Shame

Brad Pitt, Moneyball

Best Actress in a Leading Role:

Glenn Close, Albert Nobbs

Viola Davis, The Help

Meryl Streep, The Iron Lady

Tilda Swinton, We Need To Talk About Kevin

Michelle Williams, My Week With Marilyn

Best Actor in a Supporting Role:

Kenneth Branagh, My Week With Marilyn

Jonah Hill, Moneyball

Nick Nolte, Warrior

Christopher Plummer, Beginners

Max von Sydow, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

Best Actress in a Supporting Role:

Bérénice Bejo, The Artist

Jessica Chastain, The Help

Melissa McCarthy, Bridesmaids

Janet McTeer, Albert Nobbs

Octavia Spencer, The Help

Best Original Screenplay:

50/50

The Artist

Bridesmaids

Midnight in Paris

A Separation

Best Adapted Screenplay:

The Descendants

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

The Help

Moneyball

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Best Cinematography:

The Artist

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part Two

Hugo

The Tree of Life

Best Art Direction:

Anonymous

The Artist

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part Two

Hugo

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Best Costume Design:

The Artist

The Help

Hugo

Jane Eyre

My Week With Marilyn

Best Editing:

The Artist

The Descendants

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

Hugo

Moneyball

Best Visual Effects:

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part Two

Hugo

The Rise of the Planet of the Apes

Transformers: Dark of the Moon

The Tree of Life

Best Makeup:

Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part Two

The Iron Lady

Best Original Score:

The Adventures of Tintin

The Artist

Hugo

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

War Horse

Best Original Song:

“Star Spangled Man,” Captain America: The First Avenger

“Life’s a Happy Song,” The Muppets

“Pictures in My Head,” The Muppets

“So Long,” Winnie the Pooh

Best Sound Mixing:

The Artist

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part Two

Hugo

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

Super 8

Best Sound Editing:

The Adventures of Tintin

Mission: Impossible - Ghost Protocol

Rango

Real Steel

Super 8

Best Animated Feature:

Arthur Christmas

Chico & Rita

Kung Fu Panda 2

Rango

Winnie the Pooh

Best Foreign Language Film:

Monsieur Lazhar (Canada)

A Separation (Iran)

Footnote (Israel)

Omar Killed Me (Morocco)

In Darkness (Poland)

Best Documentary:

Bill Cunningham: New York

If a Tree Falls

Pina

Project Nim

We Were Here Read more!