Monday, October 15, 2012

NYFF 2012: The Case for Cinema

Cinema, as an art, is not a modern human innovation. It is not an invention. The technical means by which we conceive and project it have emerged in the last century, true, but the need for it and desire for its magic has existed since the dawn of man. Some thirty-odd millennia-old cave drawings from our earliest ancestors show buffalo with many legs, presumably to create the illusion of movement of a stampeding herd when torches of light were swayed over the pictures from side to side. In 2012, it has been proclaimed that cinema is dead. Film stock is being phased out in favor of digital cameras, which some think of as little more than small computers. It is possible now to watch Lawrence of Arabia on your smartphone. Movie theater attendance has dwindled since the onset of remote controls and VCRs.

As the 50th New York Film Festival draws to a close tonight, it’s proven to be an unqualified success. Not just in terms of the publicity gained by unveiling Oscar hopefuls like Lincoln or Flight, but in showcasing a selection of films that, in 2012, actually push the boundaries of cinematic possibility and offer an exciting and hopeful future.

The festival opened with Ang Lee’s Life of Pi, the director’s most daring venture yet — dipping his toes in 3D technology and heavy CGI amidst the thematic density of Yann Martel’s novel. The business of Hollywood seems to have appropriated such technologies in a depressingly cynical way, going so far as to retrofit 3D onto films that were made to be seen in simply two dimensions just for the sake of maximizing their profits. But Ang Lee shows us the true potential of cinematic expression possible with these new means of filmmaking. As a spectacle, Life of Pi is unmatched. The height of the film is in the turning point of the ship sinking scene, which is equally harrowing and horrifying. The film swept me up and immersed me in a theatrical experience that I could feel would be remembered fondly in 10, 15, 20 years and forward as a moment of moviegoing marvel.

It’s what one might call an “event” film, the kind Hollywood executives try to put out each Summer to keep people wanting to see films in the theater rather than illegally streaming it to their laptop through the allure of 3D and/or IMAX projection. It’s the thrill of watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master in 70mm and feeling like you’re watching a cinema in its purest form. But no director heretofore — not James Cameron, not Chris Nolan, not even Martin Scorsese — has felt out the potential for depth and spectacle with these tools more comprehensively that Ang Lee has here, not only advancing CG technology to new heights with the creation of the tiger but in cracking open new possibility for the future of film going into a digital age.

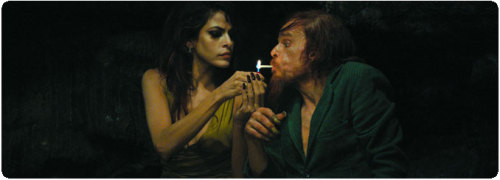

Also playing with the digital format, albeit begrudgingly, was Leos Carax’s return to filmmaking since Pola X in the 90s. Holy Motors opens with Carax himself awaking and entering a theater full of spectators as we enter his strange abstract world of a man with many worlds himself, a job of many occupations, and no shortage of faces to put on. It plays largely like a lament of this new age, between people’s abilities to be anyone they please through internet anonymity to intercuts of very early film yearning for a time when cameras were bigger than you (when now they’re smaller than your head, and everywhere you turn). Consistently mind-ripping sequences offer a feeling that they’re instantly iconic, tearing to shreds every standard of film you assume and creating a mad, nonsensical masterwork that keeps you at the edge of your seat for watching something exciting and new unfold in front of you. Sequences played out with a sense they’d instantly become iconic. You come to the safe conclusion that you never know what’s going to happen next, which is a feeling so fresh and so thrilling — to know you’re witness to a game changer. Jean-Luc Godard once noted that if cinema had never been invented, Nicholas Ray would have invented it. Suffice to say, I think the very same applies to Carax.

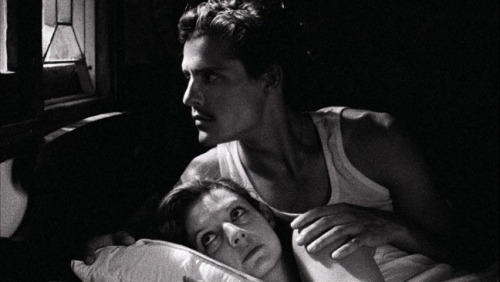

Perhaps the very finest film to screen at the festival was Miguel Gomes’ dreamily lovely Tabu. Gomes, working with film, actually uses the older tools at his disposal to paint a portrait of Western humanity between past and present, switching between 35mm and 16mm between the film’s two acts. The film in the present is in the more realistic (though black and white) 35mm print focusing on a present day woman in Lisbon whose elderly neighbor is nearing the end of her life with a maid hired by her daughter that she is deeply paranoid of. The film touches on social contexts explored in the second half of the woman’s earlier life in a Portuguese colony in Africa in grainy 16mm offering a dream-like reflection of a story that delves into unabashed melodrama that reflects on the past, its relevance to the present, and the general universality of human emotion. It works as engrossing entertainment as well as it does in its depths of commentary (pertaining to race, class, history, gender, age, etc.) and is a real achievement.

Also employing some old school film stock is Pablo Lorrain’s No, which looks like a 1980s home video cassette recording that Lorrain then brilliantly intercuts with actual archival footage looking very much the same. Documenting the “No” campaign in the 1988 Chilean plebiscite against General Pinochet, the film uses the actual television spots run on both sides and footage of protests that show the brutality of Pinochet’s regime — making so much more powerful the actual staged events of the film featuring a fine performance by Gael Garcia Bernal. The film’s fresh and fascinating use of cinema lends to a much more explicitly political message than that of Tabu, but the film is similarly so light-hearted and rather fun around its edges.

The films at this year’s festival ranged widely in genre, tone, style; some used digital, some used film. But they all unite in confirming the hope for the future of film — for its possibilities, its potential, its usefulness, and the value of still going to see movies like this in going forward. Many people seem confuse a lack of a clear future path with having no future at all. What is actually the case is something a lot more exciting, and a lot more fascinating than the more foreseeable path! People can make films at the palms of their hands and upload them to youtube. Amateurs like myself could access these works publicly and write up my own critiques of them. It can be argued, in fact, that we’re witnessing the dawn of a new emerging golden age of film. A golden age where everyday people from all around the world are creating new and interesting works of art with new and rapidly advancing formats and technologies that bring us well past the age of waving fire-lit torches across a simple painting to mimic the basic magic of a moving image, and into the 21st century with an evolving and expanding understanding of the cinematic form. Read more!

Labels:

ang lee,

cinema,

film,

gael garcia bernal,

holy motors,

leos carax,

life of pi,

miguel gomes,

new york film festival,

no,

NYFF,

pablo lorrain,

tabu

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)